A brief history of landscape painting

White Horse, Uffington, c1,000BCE

Okay, not a painting, but one of my favourite pieces of art in and of the landscape, I have seen it four or five times (on the ground) but it is only visible from the air. A figure with a shadow shows the scale. The look is similar to Celtic horse designs

A much older tradition

Indigenous art permeates the Australian landscape and often deals with the creation of that very landscape,

Jawoyn Association, which represents the local traditional owners of land south of Kakadu found this artwork. When Robert Gunn, an archaeologist brought in to document rock art in the area, saw the painting he immediately thought it looked like Genyornis, an emu-like, big-beaked, thick-legged bird that went extinct along with other Australian megafauna between 40,000 and 50,000 years ago.[1]

If confirmed, this would be the oldest rock art anywhere, pre-dating the famous Chauvet cave in southern France by some 7,000 years.

[1] https://www.australiangeographic.com.au/news/2010/06/bird-rock-art-could-be-worlds-oldest/

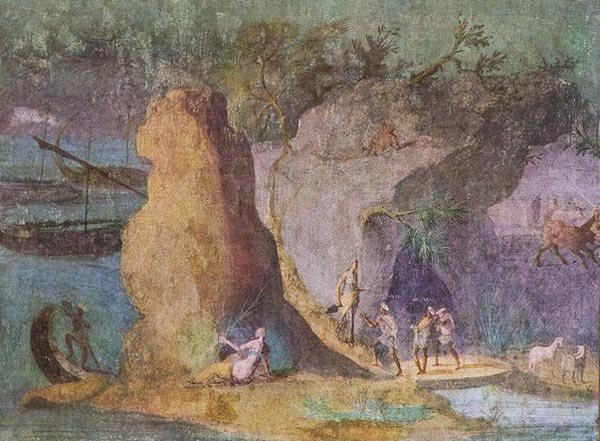

Classical landscape painting

There are a few examples surviving. This is the landscape of Homer’s Odyssey, 1st C. B.C. A version of an earlier 2nd C BCE, Hellenistic painting, from a fresco cycle in a house in Rome, Vatican Museum.

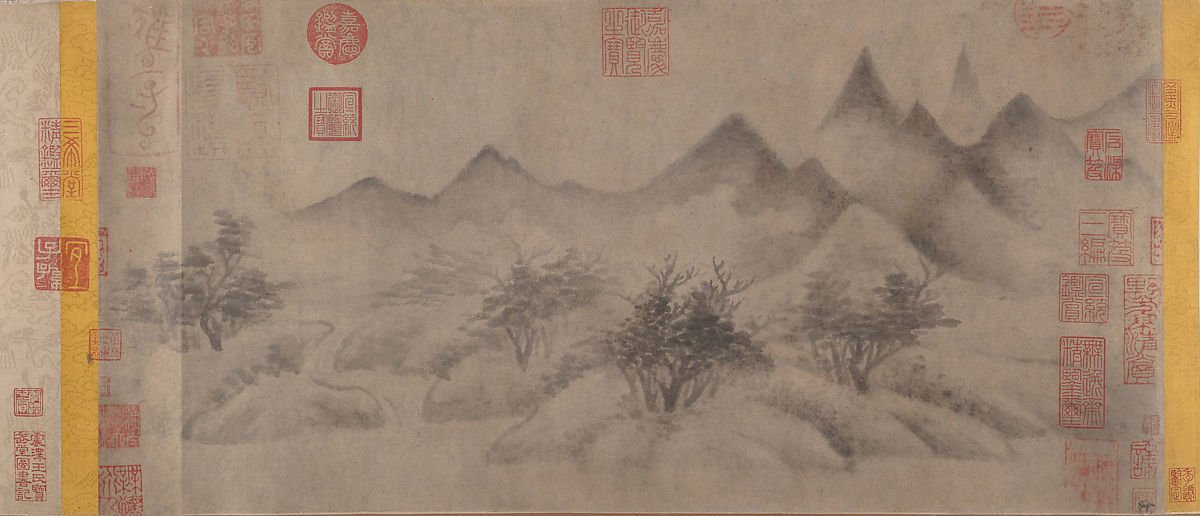

The Chinese Landscape tradition

Mi Youren was the son of Mi Fu, scholar, poet, calligrapher and painter and a dominant figure in Chinese art. This tradition was abstract, aiming for the spirit of landscape. Mountains were revered as having dragon’s veins, the manifestation of ‘qi’ ( or chi), nature’s power.

The (western) Renaissance

In the early Renaissance, landscape crept into the background of religious paintings.

This work by di Cosimo is one of the earliest landscape paintings of the Renaissance. In Florence there was a growing interest in wonders of nature. Vasari wrote: ‘He [Cosimo] would never let his garden be dug or the fruit trees pruned . . followed a away of life more like that of a brute beast than a human being.’

Joachim Patinir was ‘a good painter of landscapes’ wrote Albrecht Durer. Landscape could dominate religious themes.

This is a beautifully strange scene with no need of humans to make it vital and interesting. Altdorfer is considered a founding father of a continuously developing landscape tradition. The earliest landscape painting of a known place is his Danube Landscape with Wörth Castle near Regensburg Regensburg’ c1522 (Alte Pinakothek, Munich). The town, southeast of Nuremburg, was a rich medieval town where Altdorfer lived.

The influential Dutch Tradition

A century after the previous examples, Jacob van Ruisdael appears as a preciosu 17-18 year old, at the beginning of Dutch landscape genre. He was a contemporary of Pieter de Hooch and Vermeer, but painted depicted the energy and force of landscapes, rather than interiors. Landscape became an increasingly popular genre in Holland and his work influenced the English painters Gainsborough, Turner and Constable.

A century after Jacob van Ruisdael we have Thomas Gainsborough copying Ruisdael in the 1740s but they didn’t sell, so he moved to Bath and made his reputation as a portrait painter. This painting is now famous for the Marxist criticism of John Berger, who wrote they ‘are not a couple in nature as Rousseau imagined nature. They are landowners . . .’. But I do love this painting, for her shoes and the wheat alone.

The Welsh portrait painter Richard Wilson set up a studio in Rome in 1750 and was inspired by the Campagna and Poussin and Claude to become a successful landscape painter. He returned home seven years later and painted Welsh natural wonders, like Snowdon and Cader Idris.

Wilson attempted a precise topographical description of landscape,but sometimes added a mythological scene to enrich the viewing with a moral, emotional and intellectual message. The critic John Ruskin called him the father of British landscape painting but his work did not sell and he was forced to paint topographical scenes to make a living.

Precursors to Impressionism and the origins of plein air painting

John Constable and his contemporary J.M.W. Turner, are sometimes viewed as precursors to French Impressionism, and, by extension, the generations of modern painting that followed.

Constable loved working en plein air, outside the studio and pioneered this approach in Britain. Working rapidly on sheets of paper or scraps of old canvas pinned to the lid of a paint box held on his knees. His open air work was drawings – in pencil and oils – which were later worked up in his studio.

In 1802 he exhibited his first landscape at the London Royal Academy exhibition, and wrote to Dunthorne: ‘For these past two years I have been running after pictures and seeking the truth at second hand … I shall make some laborious studies from nature … There is room enough for a natural painter.’ [1] Yet two decades later Constable wrote to his wife: ‘I have a little Claude in hand, a grove scene of great beauty and I wish to make a copy of it to be useful to me as long as I live. It contains almost all I wish to do in landscape.’[i]

By 1819, he was showed large oils, like The White Horse (Frick Collection, New York), the first in a series of six large oil paintings depicting everyday life and work on the River Stour.

The Hay Wain was in the 1821 Academy exhibition but attracted little interest and failedto find a buyer. However, the influential Théodore Géricault saw the work and was very excited. On his return to France he praised Constable to Eugene Delacroix (who subsequently) altered his style, and the Paris-based British art dealer John Arrowsmith. Arrowsmith saw The Hay Wain at the British Institution the following year and offered £70, just under half the asking price. Constable declined. Three years later Arrowsmith visited Constable and bought four paintings including The Hay Wain, which he put in the Paris Salon of 1824. It won a gold medal even as Constable asserted that French painters ‘neglect the look of nature altogether, under its various changes’.[2] Constable’s reputation was growing in France, but Arrowsmith went bankrupt.[3]

[1] John Dunthorne, a local plumber, glazier and amateur artist encouraged the young artist. Quoted in: http://www.visual-arts-cork.com/famous-artists/john-constable.htm

[2] William Feaver, ‘Pictures are books’, The Guardian Saturday May 27, 2006.

[3] Howard Oakley, ‘Patrons & Painters: Constable’s French connection’, https://eclecticlight.co/.16.3.2020.

[i] 1823. As a guest of Sir George Beaumont, he first saw a Claude around 1800, but 23 years later he wrote to his wife . . . Quoted in signage, NSW AG, March 07. Kenneth Robert Olwig. Landscape, Nature, and the Body Politic: From Britain’s Renaissance to America’s New World. Foreword by Yi-Fu Tuan. Madison: University of Wisconsin Press. 2002.

The French

Seventeenth-century Dutch landscape artists did not paint en plein air (‘in the open air’). Ruisdael would have made sketches and painted from them and from memory in his studio. In 1848, two centuries after Ruisdael, a group of painters settled around the French village of Barbizon near the Fontainebleau forest. The ‘Barbizon School’ is focused on landscape painting en plein-air. They felt painting out of doors was more immediate, accurate and truthful and they developed a remarkable naturalism through carefully observation.

The best known are Camille Corot and Theodore Rousseau who began at a time the neoclassical tradition of Claude and Poussin still ruled. Constable and Turner (who both adored Claude) were moving painting in new directions and having an effect acrosos Europe. Rousseau worked in every medium and focused on the surrounding forests, gorges and marshes which were not necessarily sublime, beautiful or picturesque. He created aesthetically interesting depictions of nature that had been disdained before, like marshes. They spent much of their time immersed in natural environments and paying attention to the details of rural life, the seasons and changing light and colour.

‘The Barbizon painters responded to Constable’s handling of paint. The broad strokes and loose marks in Constable’s paintings seemed to record the vigorous movements of the artist’s hand, unlike academic conventions which tended to suppress those kinds of traces.’[1]

[1] Constable’s legacy and influence. https://www.tate.org.uk/art/artworks/constable-salisbury-cathedral-from-the-meadows-t13896/in-depth-salisbury-cathedral-from-the-meadows/legacy-influence

Rousseau whispered: ‘Silence is golden. . . I dare not move because silence reveals the heart of things. The woods begin to stir. Silence has allowed me, as I stood as still as a tree trunk, to witness a deer in his dwelling and at his toilette. He who lives in silence becomes the centre of the world.’[i] Greg Thomas calls him an ecological painter in that he perceived (perhaps subconsciously) the interconnectedness of nature where humans did not belong, where even painters were intruders.[ii] He also worked to preserve the area as Frances was quickly changing. Following Corot and Rousseau to the forest of Fontainebleau were Alfred Sisley, Renoir and Monet.

[i] Theodore Rousseau quoted by Liani Vardi, Reviewed Work: Art and Ecology in Nineteenth-Century France: The Landscapes of Théodore Rousseau by Greg M. Thomas, The Art Bulletin, Vol: 85: 1, 2003.

[ii] Greg M. Thomas, Art and Ecology in Nineteenth-Century France: The Landscapes of Théodore Rousseau, Princeton University Press, 2000. He preferred wilder, darker scenes to Corot, ones without humans. He had a tough life was nicknamed grand refuse’ for being rejected by the Salon fifteen years in a row until the changes of 1848.

Corot’s en plein oil sketches found no market in his lifetime, but they influenced Impressionism. In 1897, Claude Monet insisted, ‘There is only one master here – Corot. We are nothing compared to him, nothing.’[i] Corot had taught Claude Monet’s teacher, Eugène Boudin, among others.

The Pre-Raphaelites began as figurative painters, but their interest in Naturalism, the pastoral past and a focus on nature led them to work directly from nature. They were championed by Ruskin who approved of their attention to detail, their politics and their nostalgia (in the ugly face of the industrial revolution) for a bygone England. Ruskin noted: ‘Pre-Raphaelitism has but one principle, that of absolute, uncompromising truth in all that it does, obtained by working everything down to the most minute details, from nature and from nature only.’[ii]

The Pre-Raphaelite painter Millais spent three months carefully observing the life on the banks of Surrey’s Hogsmill River for Ophelia (1852). He would rise at 6, begin work at 8, and return to his lodgings at 7 in the evening. He painted the great variety of plants in meticulous detail, yet they also have symbolic meaning. Apparently, the ring of violets around Ophelia’s neck refer to faithfulness (or chastity) (or death!)

From about 1860 plein air became fundamental to impressionism and it became popular partly because in the 1870s paints in tubes became available. Previously, painters made their own paints by grinding and mixing dry pigment powders with linseed oil, a much more laborious and messy process.

The Pre-Raphaelites looked backwards and it was an American, James Whistler, who sought to reinvigorate landscape painting, in ways that Turner and Constable woudl have understood. And it was the Australian Tom Roberts who came across a show by Whistler im London, anmd was intrigued.

[i] Monet, 1897 quoted in Intro to Gary Tinterow, Michael Pantazzi, Vincent Pomarède, Jean-Baptiste-Camille Corot, Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1996, pxiv. They quote Degas too: ‘He anticipated everything.’

[ii] John Ruskin, Edinburgh Lectures, 1853.