Curlew Camp, Walk 1

January 2018

There are plenty of ruined buildings in the world but no ruined stones. Hugh MacDiarmid, ‘On A Raised Beach’

1

The agile harbour oscillates fantasies, a prime tourist destination, or a Cadigal arena rocking with women in bark canoes (nowies) fishing with shell-hooks.

2

After tens of thousands of years these waters succumbed to convict transports, ships of the line, whalers, tenders, colliers, freighters, steamers, tugboats and launches, yachts, and now speeding water taxis and a procession of ocean liners. The tall ships that clustered the working harbour and continual shuttle of ferries (Walt’s ‘living poems’) are becalmed in sepia, from when the city was manageable. Then 80% of the population lived within walking distance of the water. The city is safely tethered but keeps expanding.

3

Instead of heading uphill to the zoo, take the path on the left. Follow the foreshore and allow the bush to become wild Brazilian. These walks focus on found objects (‘objet trouvé’) living or not, which may be treated as works of art in themselves (catalysts of engagement, enjoyment and the imagination), and/or as providing inspiration, pleasure, enjoyment.

A dig could unearth unconformities: broken shells, snapped bird bones, cracked crockery, even traces of torn song. The Impressionist painters ignored the foreground, the immediate life around them, the minutiae of the everyday beneath or around their feet. The familiar fire-breathing dragons have downsized to punks, Eastern Water Dragons.

4

The remarkable Diprotodon, a wombat the size of a car, rooted round here. The Leviathan of old has been transformed into a pink unicorn taking to the water.

You would expect an everyday aesthetic to be generous and welcoming to the kitsch as well as the ordinary.

You would expect an everyday aesthetic to be generous and welcoming to the kitsch as well as the ordinary.

5

Rocks perched on the periphery are the façade of a stable world. Hard-packed in strong intermolecular bonds, the sandstone pieces are isolates lodged in a continental body drifting slowly north.

6

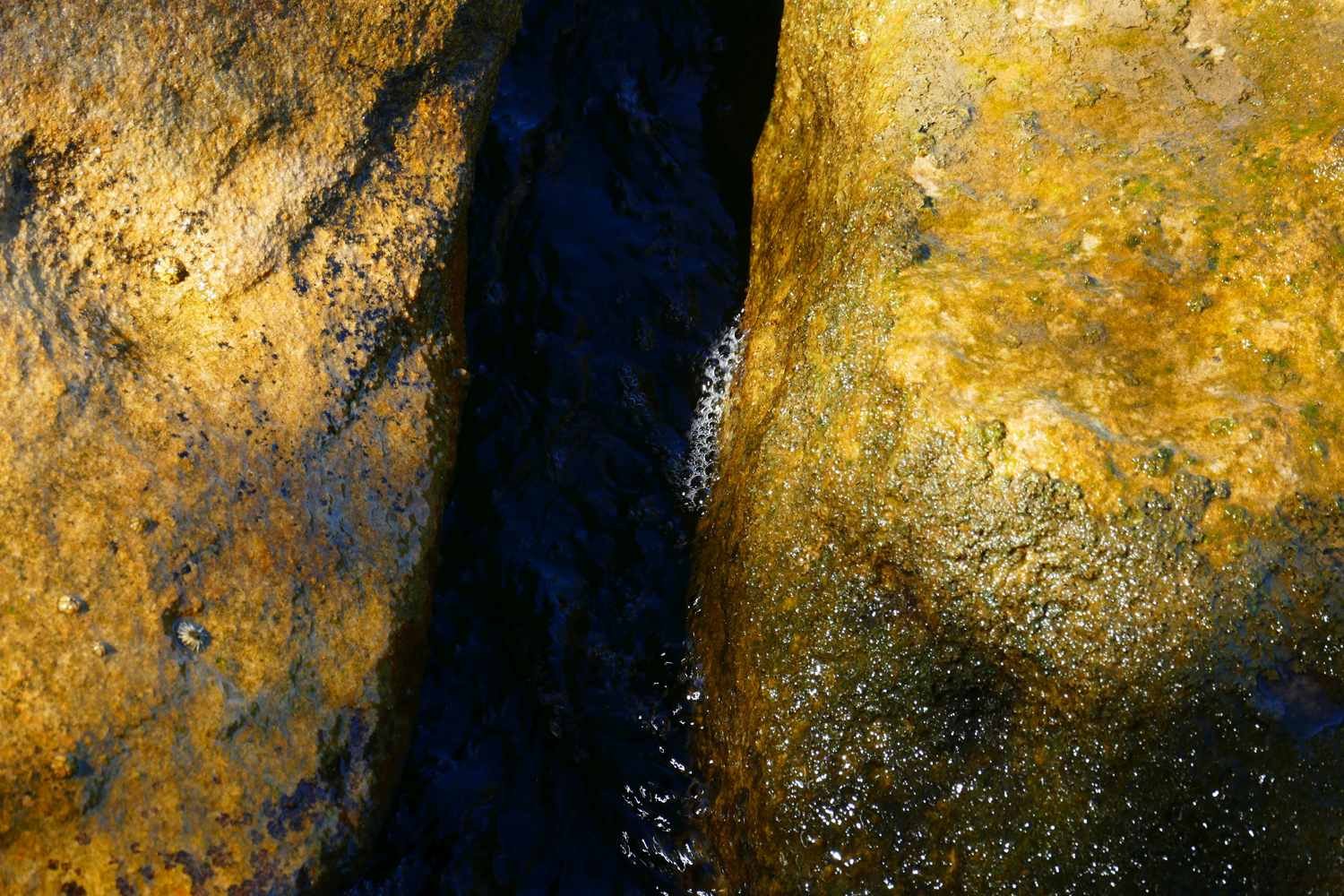

The harbour fingers drowned sandstone, loosening the surrounding skin, creased and wrinkled. Close up, the eye loses focus and follows the persuasive flow. Thales’s universal medium was not air or atoms nor paint, but mercurial water ephemeral with diversity and transformations of form – frothing, collapsing, pooling on the lips.

Cupped rock’s latent energy is swirling as if competitive Picts using the Welsh tongue had used a syllogism to beat the Portuguese and meet the neighbours first.

Cupped rock’s latent energy is swirling as if competitive Picts using the Welsh tongue had used a syllogism to beat the Portuguese and meet the neighbours first.

7

Life-lost wood / stone gift prospects / sculpture between footsteps / a worn carpet-leaf-track / a shuffle of summer scents. The rim tastes of salt.

Try and shake Cartesian dogma. The wooden stump is a reminder that trees are lives we share. Ambitious surgeons amputated limbs in Ravensbrück.

Try and shake Cartesian dogma. The wooden stump is a reminder that trees are lives we share. Ambitious surgeons amputated limbs in Ravensbrück.

8

The Sea always comes up against rock, either fine grained or thickset. The male gaze is open to a multitude, you have the edited version. A rock as a dead thing, a crouched chrysalis, a solid lyric with seductive haptic promise.

9

Rocks are essentially democratic, no need to ascribe value, parade a rhetoric of cultural capital or imagine them sitting in your garden. What would you be willing to pay?

Fingered, chiselled, sawn, no need for maquettes, each piece an abstract version, but this photograph is framed giving the illusion of order. Disorder is slipping just out of shot.

Fingered, chiselled, sawn, no need for maquettes, each piece an abstract version, but this photograph is framed giving the illusion of order. Disorder is slipping just out of shot.

10

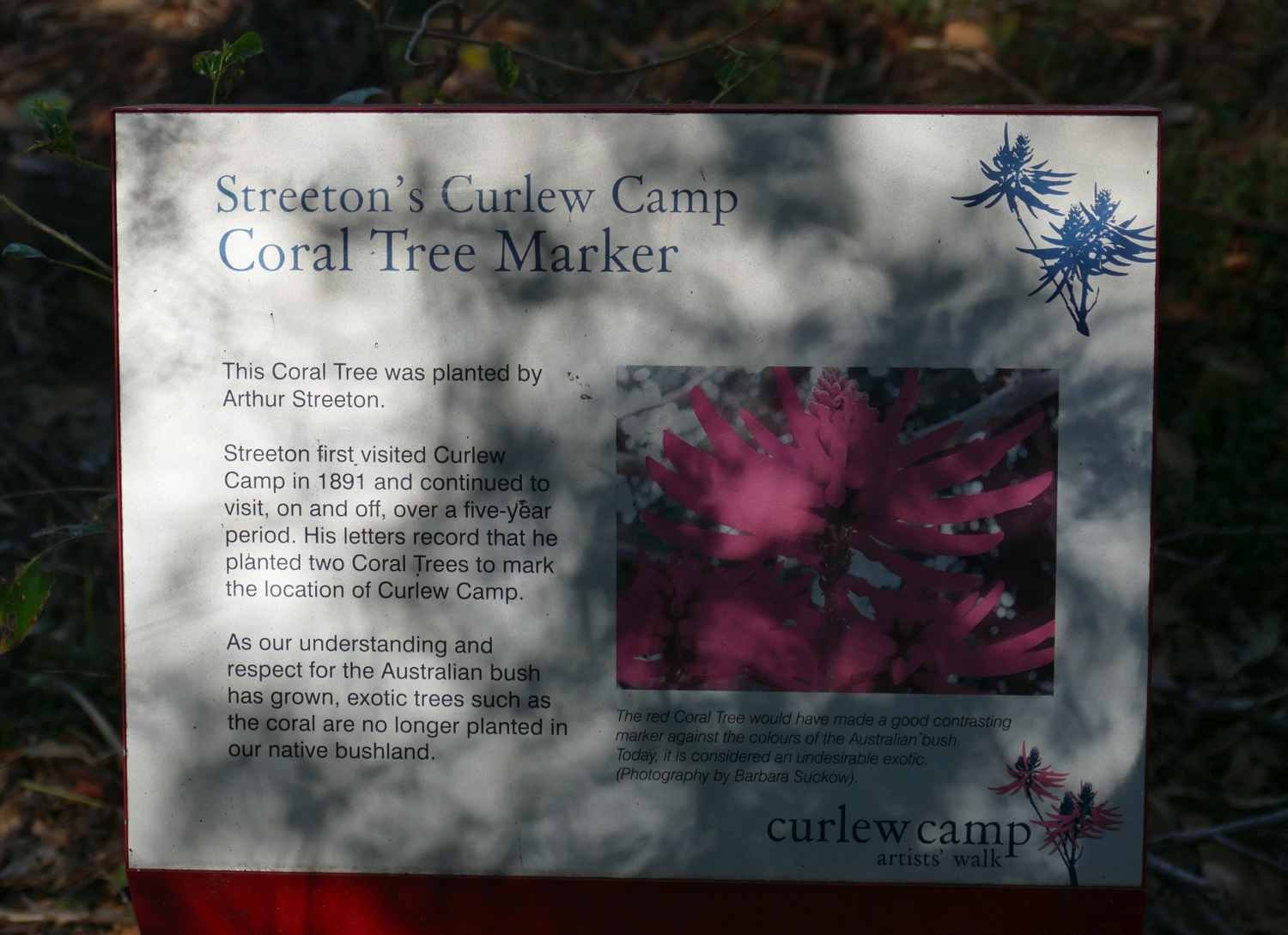

The Coral Tree, native of South America, was planted by the garden lover (but on my next visit will have been excised).

Streeton wrote, ‘Around the tent climb the Begonia and Clematis and Sarsaparilla the rough winds broken for us by an exquisite fusion of tender gum-leaf. Honeysuckle (like the trees of the old asters). Cotton plants heath and a wild cherry (bright green at our tent door) and the beautiful flood beneath. All is splendid.’ April 1891. [1]

11

Space and form seem indivisible. Surfaces operate directional movement extending out into space – angled, curvilinear, concave, convex, flat or ridged. We too display directional movement in terms of preference. Affect works with intention and a muscular impulse to act, retreat or shut out.

12

Wanted: a vocabulary of geomorphology. A poet in stony exile on Whalsay thumbed through a specialist dictionary, words heavy as ingots. Riches of language are hoarded in books.[2]

13

Their landscapes were idealised, ignoring the way the sublime was on its way to becoming urban and technological, despite all the new discoveries in the natural world. John Barrell talks of ‘the dark side of landscape’, the pastoral has always idealised rural life and concealed the harsh reality.[3]

How can artists continue to paint pretty, to repeat landscapes, when they hide the pollution, microplastics and what is happening to the soil, fauna and flora?

How can artists continue to paint pretty, to repeat landscapes, when they hide the pollution, microplastics and what is happening to the soil, fauna and flora?

14

The lens challenges my eye to find beauty and form and surprise in the ordinary. I shoot what I see, don’t use Photoshop, sometimes crop a little. One pale rock looks buoyant in the sun. If I had the strength to toss it into the harbour, it might just float. Why not otherwise?

The past is a prison continually being renovated then distressed. Symbolic representations are too easy and dangerous. The end of art is endless fractal modelling or when art ceases to be art.

The past is a prison continually being renovated then distressed. Symbolic representations are too easy and dangerous. The end of art is endless fractal modelling or when art ceases to be art.

15

John Ruskin wrote, ‘There are no natural objects out of which more can be learned than out of stones.’[4] Some of these stones have the, ‘noble simplicity and calm grandeur’ which Johann Winckelmann insisted characterised Greek art, the aesthetic ideal (somehow outside history).

As Rosalind Krauss writes, ‘We had thought to use a universal category to authenticate a group of particulars, but the category has now been forced to cover such a heterogeneity that it is, itself, in danger of collapsing. And so we stare at the pit in the earth and think we both do and don’t know what sculpture is. Yet I would submit that we know very well what sculpture is . . . But the convention is not immutable and there came a time when the logic began to fail.’ [5]

[1] Ann Galbally and Anne Grey, Letters from Smike: the Letters of Arthur Streeton 1890–1943, Oxford UP, 1989, p34.

[2] Hugh MacDiarmid’s ‘On A Raised Beach’ (1934) is a wonderful poem written on Whalsay, an island in the Shetlands. It is grounded in the elemental and is one of his first well-known poems to have been written mostly in English.

[3] John Barrell, The Dark Side of the Landscape, Cambridge UP, 1980.

[4] John Ruskin, Frondes Agrestes: Readings in ‘Modern Painters’, VI §38, 1893.

[5] Rosalind Krauss, ‘Sculpture in the Expanded Field’, October, Vol:8 Spring, 1979.