The Tennis Court Oath

Late in the 18th century, France was bankrupt. Partly due to its costly involvement in the American Revolution, a series of failed harvests, and the extravagance of the court of King Louis XVI. The cost of remodelling a hunting lodge of King Louis XIII into the Palace of Versailles is estimated to have cost over AU$3 billion in today’s money. Marie Antoinette collected clothes, jewels, snuffboxes, porcelain, furnishings, books and is said to have owned over 300,000 pairs of earrings.

As an aside, the wonderful composer Armand-Louis Couperin had died in February 1789 aged 61, in a traffic accident, knocked down by a runaway horse.

To try and solve France’s economic crisis, King Louis formed a national assembly comprising the three ‘estates’ of the French people. The First Estate was represented by the Church; the Second Estate the privileged social class. The Third Estate combined commoners ranging from wealthy merchants people to poor rural farmers.

The Third Estate covered about 97 percent of the population, but could be outvoted by the First and Second Estates, and were without the rights and privileges of the first two Estates. Privileges exempted the clergy and nobility from taxation, and reserved hunting rights for nobles. A mass of ordinances protected production rights for guilds, confined trade to particular locations, even regulated musical production from public performances to score publication to instrument building. Debate ground to a halt on the key issue of deliberation by Estate or by individual.

When the Third Estate joined by most of the clergy and an active minority of noblemen met on June 20, 1789, they found their meeting room locked. They moved to the nearby Jeu de Paume Royal Tennis Court of Versailles, a large rectangular hall with high windows. There, they collectively made an oath not to disband until they had created a constitution with equal taxation and proportional voting. This is known as the Tennis Court Oath.

Two days later, the King made concessions. He declared that the taxation system would be revised and legal procedures improved. However, he was not ready for the adoption of a constitution. This was unacceptable to the Third Estate, and they continued to defy the king’s orders and remain in session. Days later, the king compromised and ordered the representatives of the First and Second Estates to join the National Assembly, thus giving it constitutional legitimacy.

Later the King directed his troops to disperse the assembly. In response, the citizens attacked the Bastille fortress, a state prison in Paris and found only four counterfeiters, two men considered mentally ill, and a young aristocrat imprisoned at the request of his family.

After four hours of fighting and 94 deaths, the insurgents took the Bastille. The governor of the Bastille, Bernard-René Jourdan de Launay, surrendered, but he and several members of the garrison were killed subsequently. The storming of the Bastille shifted public opinion sentiment towards revolution and is now a national holiday. Members of the nobility started to leave France. Among the first were the comte d’Artois (the future Charles X of France) and his two sons.

In 1790, Jacques-Louis David convinced the Jacobin Club to launch a national subscription to fund a painting to The Tennis Court Oath (Le Serment du Jeu de paume). He exhibited a pen and brown ink drawing of his planned painting in the Louvre in 1791 having drawn all the faces in detail so that every figure was recognisable. But the subscription failed. Political reversals and financial difficulties meant that David was never able to finish the canvas, is now in the Musée National du Château de Versailles. I have seen the version in the Musee Carnavalet, Paris, thought to be painted from a drawing by the artist, who made various preparatory drawings. In 1883, the tennis court became the Museum of the French Revolution and hung Luc-Olivier Merson’s monumental painting, The Tennis Court Oath, based on David unfinished work of 1791.

The following year, an amateur musician, Claude Joseph Rouget de Lisle, wrote the words and music of ‘La Marseillaise’. (Originally titled ‘Chant de guerre pour l’Armée du Rhin’ – War Song for the Army of the Rhine).

In March 1793, the National Convention created the Committee of Public Safety to protect the newly established republic against foreign attacks and internal revolts. On September 5, the Committee of Public Safety, led by Maximilien Robespierre, officially made ‘terror the order of the day’. The Committee was the de facto executive government in France during the ‘Reign of Terror’ which lasted until July the following year when Robespierre was overthrown. In this time, an estimated 500,000 suspects were arrested, 17,000 were officially executed and 25,000 died in summary executions. The death toll during the Reign of Terror across France was about 40,000.

The rest is history.

‘Everything proceeds as if space had been trapped by time, as if there were no history other than the last forty-eight hours of news, as if each individual history were drawing its motives, its words and images, from the inexhaustible stock of an unending history in the present.’ Marc Augé[i]

Fat Man and Kermit

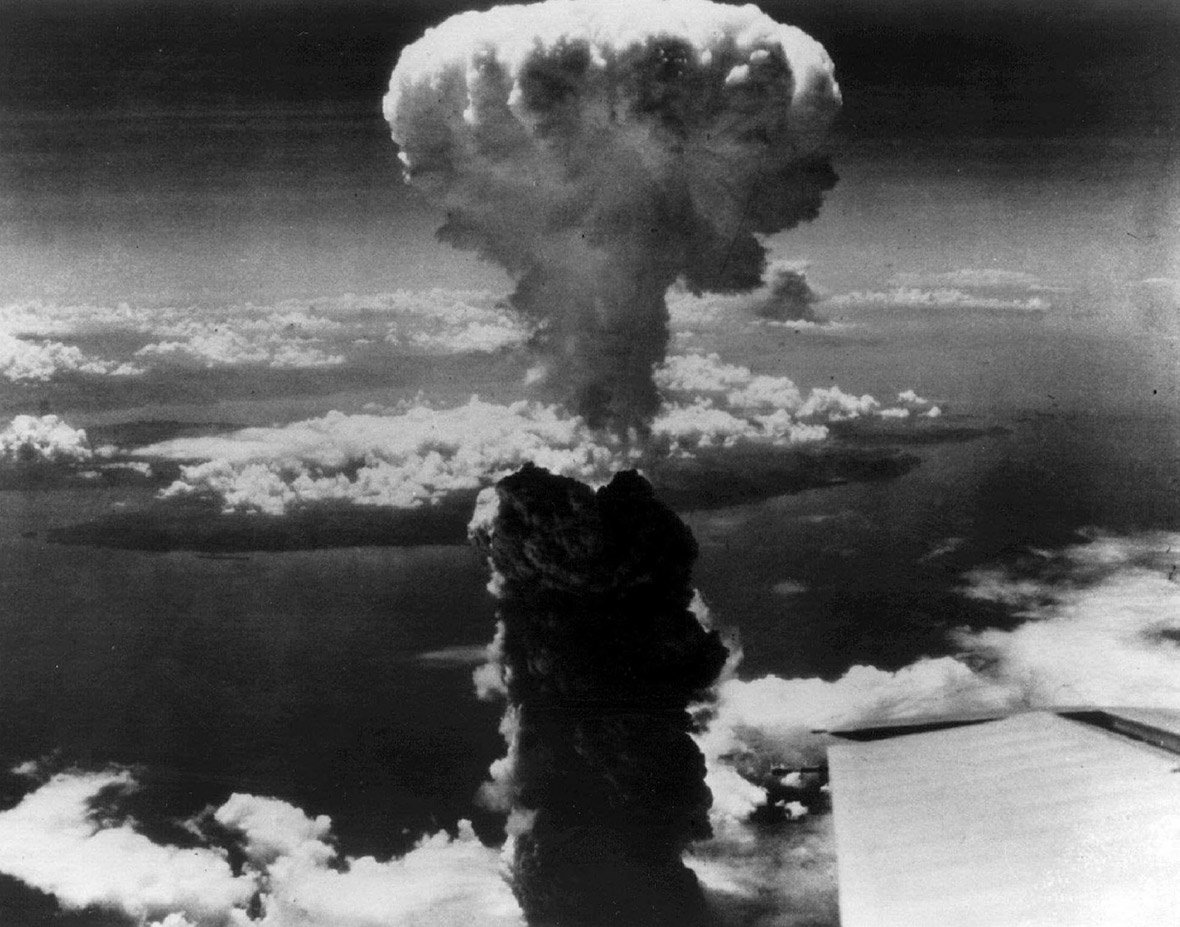

The primary target for Fat Man was a factory in the city of Kokura, surrounded by the highly populated industrial cities of Yawata and Tobata. The city had one of the country’s largest ordnance factories, manufacturing among other things, chemical. Kokura had not yet been bombed. Two weather aircraft over Kokura both reported a sunny sky, so there should have been no problem to a visual drop that day, August 9, 1945. But that’s not what happened. This was three days after the first atomic bomb dropped over Hiroshima. ‘Fat Man’ was a plutonium bomb of far greater complexity than the first. It had a yield of approximately 21 kilotons of TNT, compared to 15 kilotons from ‘Little Boy’ (uranium) which was dropped on Hiroshima.

The verbatim record of Abe Spitzer, the radio operator, reveal confusion among the crew of the B29, called ‘Bock’s Car’, as to why Captain Kermit Beahan, a renowned bomb-aimer, hadn’t released the bomb on Kokura in what appeared to be cloudless sky.

According to the intercom transcript, from the nose of the aircraft came Beahan’s cry: ‘Goddam to hell, no drop, no drop! I can’t see the goddam target! There’s cloud over the goddammed, goddamned target!’

The B29 made three bomb runs, but lying flat in his aimer’s position, Beahan refused to drop the bomb. ‘Goddam, goddam, no visual! No drop, no drop, no drop!’

With Japanese fighters now climbing fast, [the pilot Charles] Sweeney, low on fuel, set course for the secondary target of Nagasaki, 130 miles away.’ [ii]

Had the bomb exploded over Kokura, as planned, an estimated 300,000 casualties would have amassed. This compares to an estimated 100,000 deaths at Hiroshima (The most credible estimates cluster around a ‘low’ of 70,000 and high of 140,000). [iii]

Nagasaki had some cloudy but radar would have clearly outlined the city. Witnesses on the ground reported a sunny morning. At 11.02 am Captain Kermit Beahan dropped Fat Man well short of the city on his 27th birthday. The bomb exploded at an altitude of 1,650 feet over the tennis courts of Koyata Iwasaki, managing director of Mitsubishi.

Sweeney banked sharply to avoid the mushroom cloud, but were still battered by five successive shockwaves Thanks to Captain Kermit Beahan much of the blast went over the city and was absorbed by surrounding hills. And, unlike Hiroshima, there was no firestorm at Nagasaki. Instead of well over a hundred thousand casualties, there were around thirty-eight thousand.

Yosuke Yamahata, a military journalist/photographer, was sent to Nagasaki arriving the day after the blast. He spent twelve hours documenting the destruction, the only extensive photographic record of the immediate aftermath of the atomic bombing of either Hiroshima or Nagasaki. He became ill on his forty-eighth birthday an died of cancer.

‘It was truly a hell on earth. Those who had just barely survived the intense radiation—their eyes burned and their exposed skin scalded—wandered around aimlessly with only sticks to lean on, waiting for relief. Not a single cloud blocked the direct rays of the August sunlight, which shone down mercilessly on Nagasaki, on that second day after the blast.’ Yosuke Yamahata[iv]

Why was Fat Man dropped so close to Little Boy? It did not give the Japanese Government time to decide whether to surrender.

Witnesses – ‘we could see the sky’.

‘It was a hot summer’s day, pretty cloudless, and the plane came over and I looked up and I could see the glistening in the undercarriage on the fuselage and there was certain reflections. Now to my knowledge, that said to me oh, they’ve opened the bomb door and I’ve caught the reflection in the sun. And I stood looking at that plane and quite suddenly there was the most vivid, most awful flash, a terrible booming noise and a feeling of hot wind and air and then the mushroom cloud, which seemed to get bigger and bigger and seemed to be blotting out the sun. There were trees which on one side were dead white and the other side was intact, all with its foliage. I remember crossing a little tiny bridge and there were shadows in the concrete of people, shadows actually emblazoned in the concrete.’ Sidney Lawrence, British POW held in a camp on the edge of the city.[v]

‘A whitish blue light shot across the room. Then came a roar that seemed to shake the whole house. After a few minutes, the falling debris became more infrequent. The voices of people in the neighbourhood screaming and crying reached my ears. I lifted my head up and looked around to find everything completely changed. The walls had come crumbling down, with furniture scattered all about. The roof had been blown off as well and we could see the sky. . . There were many dead bodies among the debris littering the roads. Their faces, arms, and legs had swollen up. There were many dead bodies floating in the river as well.’ Yoshiro Yamawaki, then 11 years old.[vi]

Takashi Nagai, a radiologist and Roman Catholic convert, was working a few hundred metres from epicentre. He recalls: ‘We were members of a research group with a great interest in nuclear physics and totally devoted to this branch of science–and ironically we ourselves had become victims of the atom bomb which was the very core of the theory we were studying. Here we lay, helpless in a dugout! . . .

Crushed with grief because of the defeat of Japan, filled with anger and resentment, we nevertheless felt rising within us a new drive and a new motivation in our search for truth. In this devastated atomic desert, fresh and vigorous scientific life began to flourish.’[vii]

He died of leukaemia six years later, aged 43. Initially, the book was refused publication by the American occupying forces, until an appendix was added describing Japanese atrocities in the Philippines (later removed).

It took many years for U.S. government officials to publicly acknowledge that nuclear explosions produced harmful radioactive fallout. The Atomic Energy Commission insisted that fallout posed no health risks.

‘When we just slow down to notice it: yes the world is scary, yes death is inevitable, yes work whittles away the best hours of our day and the best years of our lives, yes the best thing many of us can ever dream of is the quiet serenity of a middle-class domestic life. But look! Sometimes a clear day and a good cookie come along.’ Joel Golby[viii]

Mitsubishi’s heavy effort

Mitsubishi was heavily involved in Japan’s war effort during the war. Mitsubishi Heavy Industries produced the iconic A6M Zero fighter, key aircraft for the Imperial Japanese Navy. Mitsubishi also manufactured commercial and military vessels, including the powerful Yamato-class battleships.

The Zero was one of the best fighter planes from 1940 to 1942. With a combination of unsurpassed manoeuvrability, fast climb rate and excellent firepower, they easily outgunned Allied aircraft in the Pacific during these years. And Japan probably had the best fighter pilots having been at war with China for 3 years. BUT, the Japanese designers had made the plane as light as possible, at the cost of no armour, zero protection for the pilot or even the fuel tanks. [ix]

Koyata Iwasaki led the company from 1916 until his death in 1945. The eldest son of Mitsubishi’s second president, Koyata was born in Tokyo in 1879. He studied history, geography and sociology at Pembroke College, University of Cambridge’s. Koyata recognised that loosening the Iwasaki family’s direct control of Mitsubishi would help the company grow. He made stock of Mitsubishi subsidiaries available to the public and incorporated the holding company as a joint-stock corporation.

In September, 1945, General Douglas MacArthur took charge of the task of rebuilding Japan. He tried to break up the large Japanese business conglomerates (‘zaibatsu’), to transform the economy into a free-market capitalist system. Iwasaki initially resisted, famously stating, ‘We have done nothing to be ashamed of.’ Though Mitsubishi’s mining operations, used forced labour from Allied prisoners of war and civilians from occupied territories. Mitsubishi later publicly apologised for its wartime actions and provided compensation to some of the individuals affected. Though the Mitsubishi website claims, ‘Despite Japan’s wartime policies, Koyata Iwasaki maintained a pro-peace stance and emphasised the importance of international business partnerships.’

By late 1947, the emergence of an economic crisis in Japan, together with alarm about the spread of communism in Asia, led to a reconsideration of this policy.

Koyata’s health deteriorated under the occupation, and he died aged 66 in December 1945. He left behind a poem:

Autumn, a season of great variety

A diseased goose, motionless

Lies still on the frosty ground.[x]

My tennis court oath

I usually lost, but played some shots, an occasional backhand topspin down the line brought satisfaction, but Graham went running every day and hated to lose. So, if I got on top, he would start patting the balls back high, and after a few back and forths I would lose patience and try to smash it, then swear my usual oath ‘SUGAR’ – with no thought of the Atlantic slave trade. I found satisfaction in the occasional ace, and annoyance at the sun in my eyes while serving, and the way sweat seemed to concentrate on spilling into my eyes stinging them. I was slow to dropshots, had an irresponsible 2nd serve, and my concentration could wander. Table tennis is my better game and rain never stopped play.

9 AM Fridays, I would be on the phone at work, using speed dial to try and book a court for the weekend. You had to be quick to grab onto one of the two artificial grass courts at The Sports Centre, University of Sydney. Graham was busy seeing clients in the community, but a member of the sports union, so I became Graham. I got to know Barbara on the desk quite well. On the bus one day I was on the way to work, reading as usual, and ignored a voice getting closer and louder – Graham, Graham! I looked up and it was Barbara.

Later, I played doubles in Nambucca, next to a Grey-headed Flying Fox colony. I didn’t mind the strong odour, and it worked well as smelling salt. It was slightly dangerous. The court often had fresh bat scats and occasional corpses we had to clear. A Gumbaynggirr elder told me that as a child his favourite tucker was flying fox, but he would not go near one now because of the danger of catching Australian bat lyssavirus (ABLV) from bites and scratches. This virus is closely related to the rabies virus and has a near 100% fatality rate in humans once symptoms appear.

Then I got bursitis, and now I’m being treated for cancer. I still have my racket. I don’t know if play will resume.

The Tennis Court Oath poems

John Ashbery’s controversial second book titled, ‘The Tennis Court Oath’, never mentions the French Revolution – ‘They dream only of America’. ‘‘Europe,’ the longest poem in the book, is among the most daunting. The poem reworks an old pulp novel, Beryl and the Biplane, that Ashbery chanced across in Paris, and from which he wrenched passages only to jam them together in new arrangements, much in the manner of William S. Burroughs’ cut-ups.’ [xi]

What had you been thinking about

the face studiously bloodied

heaven blotted region

I go on loving you like water but

there is a terrible breath in the way all of this . . .

John Ashbery, ‘The Tennis Court Oath’.[xii]

Christies auctioned 75 first-edition books for the PEN American Centre in December, 2014. Each was annotated with words and/or illustrations by its author. Ashbery added some copious handwritten notes to the title page of The Tennis Court Oath.

PEN American reports that, ‘The number of writers jailed reached a new high in a wider range of countries, with at least 375 behind bars in 40 countries during 2024, compared to 339 in 2023.’[xiii]

[i] Marc Augé, Non-Places: Introduction to an Anthropology of Supermodernity, (1992) John Howe trans., Verso 1995, p104-5.

[ii] Bernard Clark, ‘Did the Nagasaki bomber miss on purpose to save lives?’ The Sunday Times, August 2, 2025.

[iii] Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists, https://thebulletin.org/2020/08/counting-the-dead-at-hiroshima-and-nagasaki/

[iv] Yosuke Yamahata, ‘Photographing the Bomb, A Memo’ (1952), from: Nagasaki Journey, The Photographs of Yosuke Yamahata, August 10, 1945, Pomergranate Press, 1995.

[v] https://www.iwm.org.uk/history/voices-of-war/nagasaki

[vi] https://www.iwm.org.uk/history/voices-of-war/nagasaki

[vii] Takashi Nagai, The Bells of Nagasaki, Kodansha International,1949.

[viii] Joel Golby ‘The Mezzanine, or: The Most Important Book About Nothing You’ll Ever Read’, Granta, 2021. On the Granta reissue of Nicholson Baker, The Mezzanine, Weidenfeld & Nicolson, 1988. https://granta.com/the-mezzanine-or-the-most-important-book-about-nothing-youll-ever-read/

[ix] In a training film, Ronald Reagan played a fighter pilot explaining how to distinguish the American P-40 fighter from the Japanese Zero. Official Training film 111-TF-3302. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=uwo5uqOywFI

[x] https://www.mitsubishi.com/en/profile/history/series/koyata/

[xi] Robert Archambeau, ‘Tennis Court Oaths: France and the Making of John Ashbery’, https://preludemag.com/issues/2. ‘Ashbery spent a great deal of time on long walks exploring the city, much in the manner of the flânneur, and knew no almost no one, other than a few American writers and his partner Pierre Martory—a writer so alienated from the literary life of Paris that he rarely even sought publication. Rather than experiencing this isolation as a burden, though, Ashbery found it enormously liberating.’

[xii] John Ashbery, ‘The Tennis Court Oath’ (1957), in The Tennis Court Oath, Wesleyan UP, 1962

[xiii] Freedom to Write Index 2024, April 24, 2025. https://pen.org/report/freedom-to-write-index-2024/

Note: minutes after posting this, I saw a headline in the Sydney Morning Herald. 5 August. 1 hr ago.

Defence -‘Clear winner’: Japan wins $10b contract for Australian warships. Japanese firm Mitsubishi Heavy Industries beat its German rival and overcame concerns about a lack of export experience to supply 11 warships.