Last Saturday in Jagun, we reached the mid-section of Oyster Creek as an intercity country train passed south. The windows of the carriages are tinted orange and as the early sun hit them, almost horizontally, they blazed, as if safety glass in a furnace.

Sunday, we were doing a bird survey and then went on to up Dorrigo for a morning birding. Monday, I was down in the estuary for Eos. So today was the opportunity to photograph this event.

The sun pushed through the early clouds and I reached the creek with five minutes to spare, Wyn left me to it. The problem was I had been finishing off texts for a series of airport videos, couldn’t find my wide-angle lens and left in a hurry.

The sun pushed through the early clouds and I reached the creek with five minutes to spare, Wyn left me to it. The problem was I had been finishing off texts for a series of airport videos, couldn’t find my wide-angle lens and left in a hurry.

I clamber along the creek looking for the best view.

Check the camera. There are options I have no idea about. I am no technician. I saw a program on photography where one professional used Photoshop on every single photograph. I don’t have Photoshop. I sometimes crop, might adjust the light occasionally, but the world is too full of images to waste time.

I didn’t bring a tripod so no video, and to get the creek in I use a vertical hold. I hear a whistle in the distance and start shooting as the metal cylinder appears through the trees, no blazing sun, a wan appearance. In three days, the sun has shifted, I doubt a single photograph holds any interest.

I walk home defeated by my lack of skills, preparation, and absence of the effect I had hoped for, but quite happy. There is so much happening in the forest.

The wildflowers are all small, avoiding the wallaby’s appetites, (plenty of wallaby scats around), but lovely.

I hear Drongos, Sacred Kingfishers, Superb Fairy Wrens, and the scratchy gargling from young Kookas. I watch a White-headed pigeon watching me from a distance. Bar-shouldered Doves chase each other. We have to see the forest and the trees.

I think of the devotion of O. Winston Link. Ogle was a civil engineer and a commercial photographer who photographed steam trains in Virginia and pioneered techniques of night photography. A Brush Turkey scampers off the track, only the second one I have seen here in over a decade, but I was thinking of writing this piece, I wasn’t present in the moment, should heed Thoreau’s warning.

O. Winston Link’s ‘Hot Shot Eastbound. West Virginia 1956’ (MOMA) is one of the greatest photographs I know. The wonderful composition is jammed packed with detail, but with enough space to avoid claustrophobia, the train and its steam perfectly framed, every element pin sharp.

Robert McFarlane describes Link’s image: ‘Massive, chrome-infested cars – Buicks, Chryslers and, inevitably, Fords – line up in orderly fashion at an American drive-in cinema in the evening. From the driver’s seat of a convertible in the foreground a young man with neatly combed short hair leans across and puts his arm around a bare-shouldered woman. Their heads touch. On the distant screen a Sabre jet fighter banks to port and starts its dive. Beyond the screen, on a raised embankment to the right, a large freight train steams at speed past the parked cars.’[i]

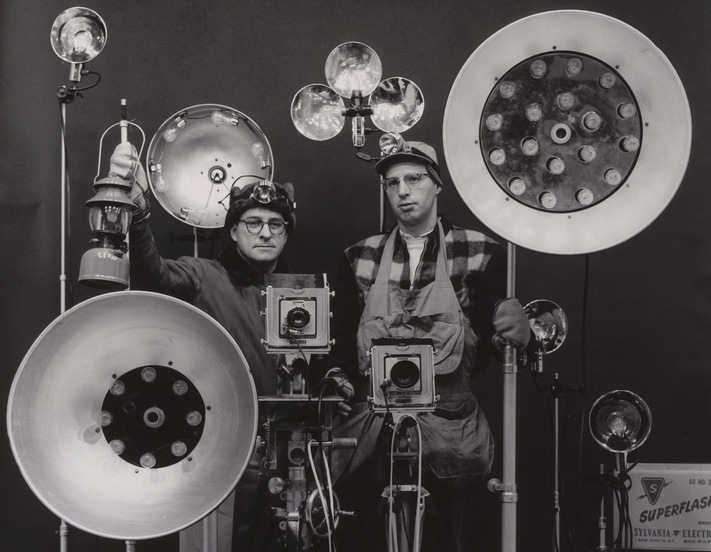

‘O. Winston Link and George Thom with Part of Equipment Used in making Night Scenes with Synchronizer Flash, March 16, 1956’ (MOMA)

This photograph shows the huge array of equipment used for a single photograph. The amount of work and planning involved is staggering. He with his assistants would spend days scouting locations, then stringing miles of electric wires for the flashbulbs. Every detail in his photographs is sharp and bright. McFarlane quotes Link’s well-known comment on achieving fame last in life, ‘I never expected that. I didn’t aim for that. All I wanted was to get some nice pictures of trains at night.

[i] Robert McFarlane, ‘O. Winston Link: Elusive rhythms of the night’, Sydney Morning Herald, October 5, 2004. ‘Link’s epic photograph also shows a train steaming into history, as Norfolk & Western was soon to become the last steam railway in America.’