29 April, VIRUS 2020

‘Rip that page out’: Indigenous leaders want to re-write Captain Cook’s landing. ABC (Gweagal and Yuin woman Theresa Ardler)

Syria war: Dozens killed in truck bomb attack at Afrin market. BBC

Stuck indoors, many of us yearn for green spaces. But scientists are only beginning to realise how much our mental health depends on the natural world. New Statesman

Putin admits PPE shortage as lockdown extended. BBC

Scientific advice recommending ban on fracking in Lake Eyre basin kept secret and ignored. Guardian

The Southern Cross is falling behind the forest

dropping stars. I see black space and hear the sea

crashingly loud, the noise present all the time,

sounding even louder from our deck last night.

The beach is moving, shifting the laws

of nature just a little in the dim occupation,

a few Soldier crabs dancing across the sand.

I try and photograph the largest, but it quickly

corkscrews, burying itself in its camouflage.

I am not feeling well, sinus perhaps, fluff

my shot of three Yellow-tailed Black Cockatoos

passing close, and the Osprey on his/her daily

commute, stopping somewhere in a tree.

The sewerage signs are still up,

I am alone, waiting for ignition.

I take a stop at my Banksia pissoir.

I’m standing in the water, a cold touch

even as the sun squeezes between cloud.

In no hurry to photograph the Striated Heron

still looking for Soldier Crabs, I find it gone.

The Osprey was perched where I guessed,

surveying its kingdom, top predator, carnal,

the dead wood a palace positioned to view

the sea lick the sand. . .

. . . My lens intrudes,

the bird glances down than away, disinterested,

crouches, shuffles the wings then is back

to intense alertness, taking everything in,

a state of attention to creation.

You sit in her stare.

You dare not stir.

I think of Ted Hughes’ poem ‘The Moon-Mare’, but this bird is mostly ignoring me,

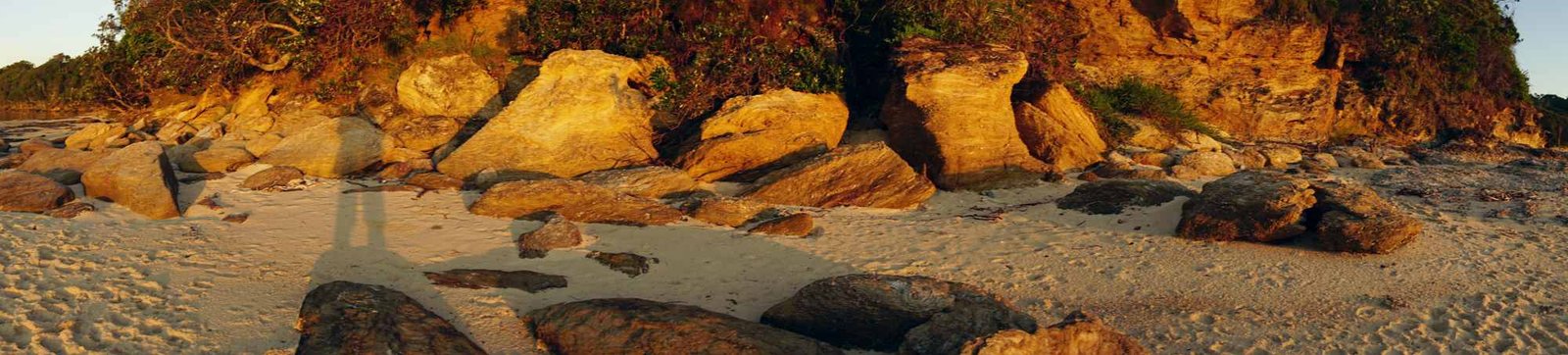

The first light uses its red fingers to interrogate the sandstone.

~

Nambucca – a walk finds a pair of swallows

and across the river, a couple of Whistling Kites

strafe a pair of Masked Lapwing skedaddling loudly.

A Pied Cormorant flies down river, single-minded,

streamlined, skimming so close to its reflection

that the wingtips tickle the water.

Daily miracles of life living lives surrounds us.

Daily miracles of life living lives surrounds us.

After lockdown, praise and thanks, and enquiries,

rebuilding, building, the carnage will continue.

I hate the sound of bandsaws and chainsaws.

Before Cook and way after the indigenous peoples of this continent

In 1697 William Dampier sailed to Australia in the pirate ship Cygnet and made the first landing by an English explorer in Australia. The spot where he came ashore is to be renamed Dampier’s Landing, in his honour. It is likely that on this voyage he collected two plant specimens, an Acacia and Synaphea. Two years later, in 1699, sailing in HMS Roebuck, Dampier landed on Dirk Hartog Island in W.A., and made a collection of specimens of flora, as well as drawings of birds, fish and other animals of the ‘New World’. Dampier had been searching for any sign of the Tryall, an English vessel which had been shipwrecked in 1622. He was one of 42 European landings and sightings along the Australian coast prior to James Cook (not to mention the Macassans, Sulawesi trepangers who traded with Aborigines along the northern coast as early as 1700).

Cook underway

(Extracts from Encounters written for Encounters, Coffs Harbour Regional Art Galley, April 2017.)

The Empress of Russia wanted to meet

the farm labourer’s son who climbed

the jagged edge of Roseberry Topping,

a Jurassic sandstone cap trapped

on the edge of the moors to watch

the Whitby Cats, working colliers,

sail back and forth to London.

He showed promise and patrons noticing

that promise sent him to school

then apprenticed him to a shipbuilder.

He first sailed in the Freelove, a Cat,

a common cargo ship bustling through

the rough churn of the North Sea.

After eight years he was offered a ship,

instead, headed south to London

to join the Navy as an able seaman.

Two years later, on his 29th birthday,

by now promoted to Master’s Mate,

he signed on the Pembroke to fight the French. . .

In 1497, the navigator John Cabot (Giovanni Cabotto)

sailed west on the Matthew from Bristol for Asia,

found New-found-land and claimed it for Henry VII,

the first Europeans since the Norse had lived there.

Cook spent years charting its coast, important

for the Grand Banks, shallow plateaus on

the North American continental shelf where the cold

Labrador current moving south sometimes stirs

the Gulf Stream’s tepid waters, conditions creating

the world’s richest fishing ground.

(Joseph Banks one of England’s richest men

happened to be there bagging natural history.)

Cook’s accuracy with charts and navigational skills

attracted the attention of his superiors. That is why

this man of common birth was chosen to lead

the expedition to observe the transit of Venus . . .

The idea was to time the transit and calculate accurately

the distance of Venus from the Sun from which distances

to other planets could be ascertained and the scale of

our solar system. The transit takes up to 6 hours, but

has to be measured within a second for useful results.

The Black Drop effect from atmospheric turbulence

fogged the image of Venus screwing their measurements.

It was a failure. Cook opened sealed orders – sail south 1769

and west, search for Terra Australis Incognita, and

‘with the consent of the natives take possession|

of convenient locations in the name of the King.’

They set sail after two crewmen were given two dozen lashes

for being ‘strongly attache’d’ to two girls and deserting.

The surgeon’s roll call found 24 seamen and 9 marines

with lesions (either syphilis or yaws, a close cousin).

Herman Melville arrived on an Australian whaler 1841

and set his novels Typee and Omoo in the islands:

Were civilization itself to be estimated by some of its results,

it would seem perhaps better for what we call the barbarous

part of the world to remain unchanged. Herman Melville, Typee

For six months they charted New Zealand’s two worlds,

tiring, methodical work. The crew had to stay alert

and work the sails. A traditional 2-watch system

of 4 hours on, 4 hours off wrecked a good sleep

so Cook introduced three watches. Still, their hammocks

rubbed against each other and the ship heaved on heavy seas.

The men drank and smoked, kept pets, carved timber or bone.

In the calm, Cook busied his crew with small arms practice

and cleaning the ship, maintaining 30 kilometres

of spider rigging and 28 sails spreading

nearly a thousand square metres of canvas.

Cook set course for Van Diemen’s Land which Abel Tasman March 31, 1770

had detected on his way to New Zealand. Gales threw them north.

I have named it Point Hicks, because Leuit Hicks was the first who discover’d this land. April 19

Zachary Hickes was Cook’s second-in-command. Having sailed west

from Europe they’d left Greenwich time behind, so it was 20th of April

and Point Hicks is mythical, has never been found. Possibly, Cape Everard,

but that means his latitude and longitude were way off, unlikely for Cook.

Perhaps the first sighting by Cook of Australia was a trick of the light?

A two-masted wooden yawl was launched off the Illawarra near Woonona April 28

(derived from the local language for ‘Place of young wallabies’ or ‘run now’).

They: pull’d in for the land to a place where we saw four or five of the natives

who took to the woods as we approachd the Shore which disapointed us

in our expectation we had of getting a near view of them if not to speak

to them but our disapointment was heighten’d when we found that we

no where could effect a landing by reason of the great surff

which beat every where upon the shore . . .

~

I was in high school in Year 10 studying Cook, and we were reading a book that said the bullets were fired over their heads. I remember getting up in my class and saying, ‘this is wrong, this is not the true history’, because my grandfather was shot. “I said everyone needs to rip that page out of your book. Gweagal and Yuin woman Theresa Ardler. [1]

There is no taking away of the significance of James Cook, clearly as an amazing explorer. However, history shows that when lands are invaded a lot of the true history is either wiped out or misrepresented. Ray Ingrey, La Perouse Local Aboriginal Land Council [2]

~

Cook met his wife Elizabeth while lodging at the Bell Inn,

Execution Dock. She was the landlord’s daughter, 13 years younger.

They spent 4 years of their 16 years of marriage together,

is this one version of how perfect a marriage could be?

I wonder how they parted, teetering on the edge of years,

becalmed and stormy, dangers and horrors lying in wait.

Did he nod then turn away abruptly, a busy man,

obsessed and dedicated, or to hide a tear feeling

foolish in front of the men, or have time to watch

her shrink as the shore retreated and distance wiped

her features until the figure submerged into landscape.

I wonder how they met again after near three years

of daily counting. He was a hardened explorer who

had been to war and witnessed bloodshed, and fresh

scenes of beauty and amazements, so I can’t give belief

to a novelist: ‘She felt the softness of his lips on hers,

the play of fingers, the trembling of their bodies

as they recharted each other.’[i]

Elizabeth buried all six of their children on her own,

three as infants, a teen and the two eldest boys

dying young in navy shipwrecks. It took 11 months

for news of her husband’s death to reach her.

She lived as a widow in black in a house crammed

with memorabilia. He wrote her a letter a week

and on each return would give her the bundles

of his love. In her 90s she burnt them all.

I take a Zytec, but don’t like feeling different anymore.

~

On the radio I hear of a survey of 2,300 people

confessing to be bored, anxious, confused (a week ago).

People now, Norman Swan suggests are beginning

to focus forward and wondering what will happen.

[1] Isabella Higgins and Sarah Collard, ‘Captain James Cook’s landing and the Indigenous first words contested by Aboriginal leaders’, ABC, 29 April https://www.abc.net.au/news/2020-04-29/captain-cook-landing-indigenous-people-first-words-contested/12195148

[2] Isabella Higgins and Sarah Collard, ‘Captain James Cook’s landing and the Indigenous first words contested by Aboriginal leaders’, ABC, 29 April https://www.abc.net.au/news/2020-04-29/captain-cook-landing-indigenous-people-first-words-contested/12195148

[i] Marelle Day, Mrs Cook, Allen & Unwin, 2002, p158.